When NOI was in office, the fuel subsidy was arguably the thorniest issue she tried to reform during both terms as Finance Minister.

Bear with me as I continue down this finite, relevant rabbit hole . . .

NOI’s Economic Advisory Team realized during their reform program — to improve the oil sector and create more jobs — that a major stumbling block to the entry of new refineries and the privatization of existing ones was the existence of a price subsidy at the pump.

Given Nigeria’s abundant oil reserves, the fuel subsidy notionally exist[ed] for the most poor and vulnerable of society to access affordable fuel.

Due to the burden the subsidy placed on the government’s spending budget, NOI believed phasing it out would be best in the long run. Its phase-out would let the true market price prevail — from N34 to N48 per liter, leading to about $1 billion saved in government spending. This would be redirected to benefit the poorest in society by re-allocating the savings on a mass transportation program (similar to the BRT system in Lagos State for instance). Another alternative discussed was introducing kerosene subsidies which would also benefit the less well-off in society given it is their main source of cooking fuel.

It is clear that the policy changes would, on balance, benefit the less well-off, more so than continuing with the fuel subsidy.

If only life was so simple.

It wasn’t the less well-off that were to be impacted by the phasing out of the subsidy, rather it would be the car-owning middle and upper classes Neighboring countries, including Benin, Cameroon, Niger and Togo, were also major beneficiaries. Nigerian gasoline was plentiful in those countries, where it fetched higher prices. An illicit trade with strong vested interests had emerged around the fuel subsidy.

In July, August, and September of 2004, during the budgetary preparation process for 2005, NOI recommended that the government completely phase out the oil subsidy. She recognized this would be a decision of great political sensitivity, requiring serious backing from the president.

Past attempts to phase out petroleum subsidies in Nigeria, in conjunction with various IMF programs, had never succeeded and had always ended up spurring violent demonstrations, sometimes resulting in some fatalities. Though she believed news of the Nigerian Economic Team being behind the recommendations this time round would mute protests, unfortunately this wasn’t the case.

Once the team had made the case to the president and the proposed phase-out entered the political realm, they were locked out of stealth discussions between appointed political spokespeople and labor which didn’t go anywhere. The team recommended the rationale be communicated to the public and especially to the more volatile stakeholders in society, such as university students and the labor unions.

However, no communication programs were implemented. Contrarily, rumors began to circulate of a pending increase, leading to hoarding behavior and queues. Though the phase-out was targeted for November 2004, while NOI was out of the country, an announcement was made in her absence that there would be an increase in the price of fuel at the pump.

Demonstrations and marches immediately ensued, led by labour and involving civil society and students. The demonstrations lasted for days and unfortunately turned violent. The police responded with force, and six people were killed. This was one of her lowest points in the three-year reform effort.

With hindsight she recognized that the reform would likely not have passed without protests, but she never felt it would result in the loss of lives. She subsequently fell into depression for days, convinced the subsidy phase-out could have been prepared without the incurrence of death.

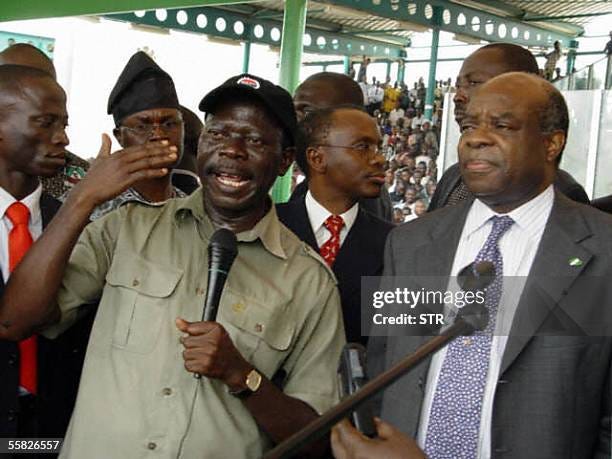

Despite the adverse developments, to his credit, Obasanjo remained politically committed to the subsidy phase-out and did not relent in the face of pressure. Labor, led by Adams Oshiomole, then of the Nigerian Labour Congress (and later politician, Edo State Governor and Senator of the Edo-North district), continued to insist it would not accept higher fuel prices and that some compromise should be found.

The president responded by setting up a working group made up of government officials (including NOI), legislators, labor, and representatives of civil society to forge a way forward. One proposal was for the group to consider imposing a small consumption tax on fuel prices when they were low. The accumulated tax receipts could be used as a cushion to stem rapid price increases when oil prices became high. Ghana and other countries experienced success with this policy, but nonetheless no agreement was found in the working group.

In addition, the Economic also emphasized how beneficial it would be to subsidize the purchase of large buses for public transport in both rural and urban areas. States were encouraged to co-sponsor and co-finance the bus-purchase initiative in their states — clearly accounted for in the federal budget. In taking this approach, the team hoped to open up the sector to entry and competition by private oil refineries.

Unfortunately, the success in phasing out generalized petroleum products subsidies and replacing this with targeted kerosene subsidies for the less well-off only lasted for one year — 2005. By the end of that year oil prices on the international market climbed higher, pushing the prices of refined products even higher. The price of a liter of petrol at the pump had gone from N48 to N65 — a 35 percent increase. To put all this onto the consumer was considered politically difficult and unfortunately subsidies crept back. Six years later, in 2011, petroleum products were still a key feature of the Nigerian economy — totaling $13 billion annually. Since this point, save for media coverage on Dangote’s [proposed] refinery, which was NOT operational, collectively no meaningful entries into the oil refinery business were made.

Round II — No Good Deed Goes Unpunished

NOI’s second round as Finance Minister made it a total of seven years that she served her country — 2003−06 and 2011−15. It far exceeded the global average tenure of two years, something the twelve-year veteran British Finance Minister / Chancellor of the Exchequer and former Prime Minister Gordon Brown disclosed to her during one of their encounters.

After all, this is unsurprising given the risky nature of the job and the propensity to say NO! whether to colleagues, cabinet ministers, civil servants, politicians and even their boss, the president or prime minister.

The dangers that come with the territory are replete. However, some dangers are more equal than others . . .

The following passages from NOI’s book, FIGHTING CORRUPTION IS DANGEROUS: The Story Behind the Headlines, are as instructive as it gets:

‘It was December 9, 2012, a Sunday, between 3 and 4 in the afternoon. I was standing in my bedroom in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, reflecting on how tired I was after working through the night on Ministry of Finance issues and missing church in the morning — a bit of a cardinal sin in ultra-church-going Nigeria. Then my cell phone rang. It was my brother Onyema with some terrifying words — words that made no sense to me at the time. “Mummy has been kidnapped,” he said. “What did you say?” I asked him, stunned. And he repeated, “Mummy has been kidnapped.” My response was sharp. “Kidnapped?” I said. “What do you mean? Where and by whom?”’[i]

Developments unfolded quickly, following her 83-year-old mother’s return from church. While in discussion with domestic staff,

‘A man had jumped out of the car, asked if she was the minister’s mother, and on receiving the answer yes, hit my mother in the face, pushed her into the back of the car, and zoomed off.’

The news left NOI “paralyzed.”

She had become aware of a trend of kidnappings that had begun recently, but never imagined her parents would be the subject of such. This was particularly the case in light of her father’s nobility as a traditional ruler (Obi) of the Ogwashi-Ukwu kingdom. Surely this social status would offer the family some form of protection, no?

As her thoughts raced, she was enveloped with a sense of guilt and panic.

Inevitably, sleeplessness enveloped the entire family who remained in a state of paralysis.

As her mind continued to work overtime,

‘The first question was, who could be behind this?

‘I knew that the largest vested interest that I had recently offended in my anticorruption work was an unscrupulous subset of the country’s oil marketers. With the President’s support, I had convened a task force that audited their fiscal accounts, detecting fraudulent claims for oil subsidy payments that I, with President Goodluck Jonathan’s backing, had refused to pay.

‘Could they be the ones behind this?

‘Or could it be those benefitting from pension payments or even judgement debt scammers whom I had blocked?

‘Could it be politicians who were displeased with fiscal reforms or could it even be those trying to block emerging reforms in the ports and customs areas.

‘Everywhere I looked, I seemed to have tread on so many toes that it could be any of these groups out for revenge. . .’

[i] Okonjo-Iweala, FIGHTING CORRUPTION IS DANGEROUS: The Story Behind the Headlines, (The MIT Press: Cambridge|London, 2018), pp.3